What a sweet film! When I accidentally deleted my notes (sigh) after seeing it the first time, I watched it over again near-immediately without any decrease in enjoyment. This script feels unusually thoroughly crafted, perhaps because it was adapted from P. L. Deshpande’s play Sunder Mi Honar. (Though my Marathi Googling skills were insufficient to uncover when the play had first been written, I did confirm that it remains both in print and in the repertoire today.) Akhtar-ul-Iman wrote the Hindi screenplay. Not only does Aaj Aur Kal reflect the constrained settings of a stage play, comparatively little actually happens in it—particularly for a film set during a recognizable, inherently dramatic historical juncture. That which occurs is largely confined the selves of its characters, miniscule actions and decisions that add up to something pleasantly life-affirming. If I were only allotted one word of description, I would call it “gentle.” Aaj Aur Kal was directed and produced by Vasant Jogalkar for Panchdeep Chitra.

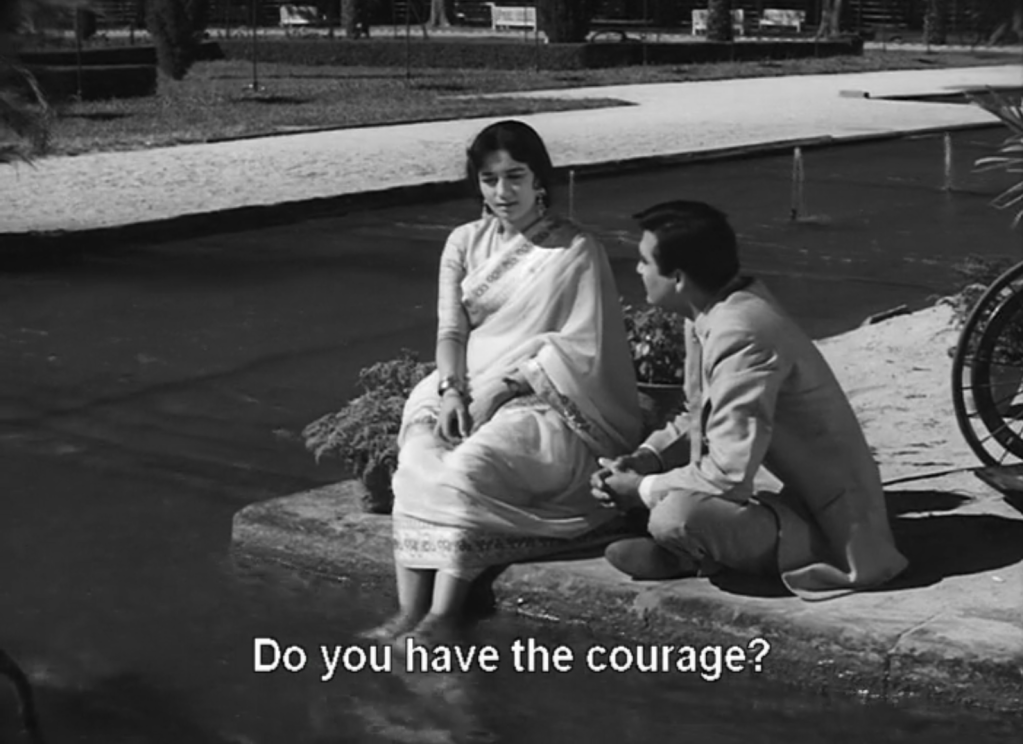

Most of the action takes place in the home of Maharaja Balbir Singh of Himmatpur (Ashok Kumar) during the first couple years of India’s independence. Upstairs is eldest child Hema (Nanda), confined to bed with mysteriously atrophied legs and harboring no interest in being cured. Downstairs, the younger three—Prataap (Rohit), Aasha (Tanuja), and Rajendra (Deven Verma)—go increasingly stir-crazy within a tightly regimented household. None are to the point of outright rebellion against Balbir Singh’s insistence on dignity or good manners, though Aasha is coming very close. She has a habit of sneaking out to meet up with her sweetheart Randhir (Soodesh Kumar), a newspaper editor and Congress Party agitator who can occasionally be spotted closer to home, leading protests on the mahel’s lawn. Into this situation intrudes Dr. Sanjay (Sunil Dutt), the latest entry in a five-year parade of specialists farmed in to attempt treating Hema’s ailments; he is the first of the doctors to view her problems as essentially psychological. Just as Hema is making some headway in her treatment, Balbir Singh returns from a conference with the new government in Delhi, which has just annexed Himmatpur into united India.

Though I scarcely feel qualified to comment on its historio-political aspects, Aaj Aur Kal sets up a clear transmission between the microcosm of the family and the macrocosm of the state. As India democratizes, the family opens up, too. In an early interaction with Balbir Singh, Randhir tells him that every weak and suffering creature is afraid of the powerful; this is the reason they ran away from you. Though Randhir had meant to refer to a group of dissatisfied farmers, the statement applies equally well to Balbir Singh’s children. The majority of the film’s runtime is spent in the smaller of these spheres. Glimpsing only snippets of the injustices enforced by the princely states lends something to their imagined enormity. Balbir Singh’s influence on his own family is demonstrably catastrophic, yet by comparison to the other rulers at the Delhi conference—much less ridiculous Dhanak Singh (Agha), who turns up in Himmatpur to court Hema—he is not malicious. His intentions are to do right by people, even if his conception of “rightness” is immovably rigid; in short, we understand that it could be much worse. These gears generally but do not always operate in tandem. Though Hema’s health mirrors that of the community for much of the film, there is a real threat that, while the rest of Himmatpur has attained a kind of homeostasis, she will still be wasting in seclusion in the mahal.

She doesn’t. I love this film’s particular flavor of optimism! Hema ultimately decides that there is no inherent value in her suffering—that pursuing happiness, even of a temporary and imperfect nature, is worthwhile. Her family has made assumptions about what would be salutary for an invalid: rest, quiet, bland food. Hema had also been practicing more personal, elective forms of renunciation besides the unpleasant regimens imposed by her various caretakers. It takes the external impetus of Sanjay to point out that, frankly, none of that had been working, so she may as well paddle her feet in the fountain if she feels like it. I can envision some viewers disliking the device of Sanjay, preferring if Hema and her siblings had been a little better fitted to rescue themselves. I don’t mind it. Quite by coincidence, shortly after watching this film for the first time, my attention was brought to a passage of Gemara:

R. Hiyya bar Abba fell ill. R. Yohanan went to him and said: Is your suffering dear to you? R. Hiyya replied: Neither this suffering, nor its reward. R. Yohanan said to him: Give me your hand. He gave him his hand and R. Yohanan stood him up.

R. Yohanan fell ill. R. Hanina went to him and said: Is your suffering dear to you? R. Yohanan replied: Neither this suffering, nor its reward. R. Hanina said to him: Give me your hand. He gave him his hand and R. Hanina stood him up.

The Gemara asks: Why? Let R. Yohanan stand himself up.

The Gemara answers: A prisoner cannot generally free himself from prison.1

Berakhot 5b: 10-13

(And in Sanjay’s defense, though pretty bland, he’s not exactly a pre-perfected doctor ex machina; indeed, he spends a long time misjudging both the cause and the extent of Hema’s affliction.)

Having Sanjay around as a viewpoint character helps sympathize Hema, too; she’s a surprisingly hard-edged heroine. Particularly early in the film, Nanda has a difficult task to fulfill in making the audience feel anything than disdain for her character, who is so clearly making her life harder than necessary and then taking the pain out on others. It helps to see her behavior from an outsider’s perspective, someone to whom she is both a stubborn patient and a struggling, suffering creature. Nanda really sells Hema’s gradual recovery of joy, and whenever she regresses closer to her original avatar, it hurts to watch. Nanda also has a great rapport with Ashok Kumar here, even if their characters’ relationship is desperately sad. Balbir Singh is the one person who, prior to Sanjay’s advent, can manage to cajole Hema into some degree of compliance with her nurses. He inquires at every mealtime whether he had eaten and invariably excuses himself from the dining room to go upstairs and intercede with her. Suffice to say that Hema comes by her petulance honestly! Time and again he leverages her obedience against her; all her worst decisions are made with his hand in her hair. Much though I respect the central performances, though, it is surely Tanuja who brought me the most enjoyment in this film. Aaj Aur Kal has a lot of humor in it, mostly courtesy of her irrepressibility as Aasha. She is light and life and makes a good comic duo, from time to time, with Deven Verma.

The songs by Ravi, with lyrics by Sahir Ludhianvi, are all beautiful and surprisingly varied. In the comedic line, there is “Ba Adab, Ba Mulahisa, Hoshiyaar.” Aasha, having learned that Balbir Singh will be away in Delhi indefinitely, runs wild around the mahal celebrating her temporary freedom. Prataap plays an obviously noncommittal straight man to her and Rajendra’s shenanigans; although they aren’t exactly in the song itself, even the functionaries and servants can be observed enjoying this unexpected holiday. Late in the film comes the political song “Takht Na Hoga Taj Na Hoga Kal Tha Lekin Aaj Na Hoga,” which is not only stirring but stylistically distinctive. I can’t think of another filmi song from this era that has so many passages of vocal harmony in it. If there is a standout song from this soundtrack, though, it would surely have to be the well-known “Yeh Waadiyaan Yeh Fizayen Bula Rahi Hai.” Though I had heard it plenty of times in isolation, within the context of the film this song is even more touching, especially that soaring middle verse “haseen champai pairon ko jabse dekha hai.” An idea that would ring superficial in another context is, from Hema’s perspective, spiritually generous: that the whole natural world welcomes a body that she is accustomed to thinking of as useless. “If you don’t listen to me, at least listen to that.”

1 From the translation by R. Adin Even-Israel Steinsaltz, although I have excised most of the gloss as superfluous; the original may be read here.

I watched this one many, many years ago, so I remember only the rudiments of it. I love the way you dissect Nanda’s character in this, especially – makes me want to watch it again just to see that.

LikeLike

I expect you would like Nanda in it! Hema’s decisions are frequently self-destructive, but she’s certainly not one of those pushover heroines, nor particularly weepy ( ; And, like everybody else in this movie, she gets her happy ending. This whole film delighted me, as you can probably tell!

LikeLiked by 1 person

And Tanuja! I noticed that you also liked Tanuja, which is another plus for me. 🙂 I love bubbly, outspoken Tanuja.

I do need to rewatch this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh!

Sounds interesting.

And I know the Marathi play as well.

Should watch it.

Thank you for the review.

Anup

🙂

LikeLike

I was hoping that some Marathi-speaking friend such as you might notice this post ( ; While looking for information on the play, I found this filmed performance with Vananda Gupte, Sriram Lagoo, Girish Oak, etc.:

I enjoyed watching some of it, despite my lack of understanding!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh!

Thank you for the link.

I haven’t watched it for a long time.

🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I finally watched this movie and thoroughly enjoyed it! Your review made it even better. Nanda’s progression is amazing to watch and yes when she retreats it is heartbreaking. I think you described it perfectly when you explained the movie in terms of showing the “microcosm of the family and the macrocosm of the state.” Tanuja was my absolute favorite. She is such a breath of fresh air and like others have said, I love outspoken (“moofat”) Tanuja!

Finally, let’s chat about P.L. Deshpande. He is more commonly known as PuLa Deshpande by people in Maharashtra. I don’t know any Marathi people who are in their 50s to 70s (especially those who might have studied in a Marathi-medium school, including my mother and most of her family) who had not grown up reading PuLa Deshpande, or watching his plays (“naataks”). Even when we moved to America, my mother’s prized possessions were old VHS tapes of Pula Deshpande’s naataks and every time we went to India, we had to purchase more of them for her.

Sundar Mi Honar (I am pretty sure Sundar is spelled incorrectly in the beginning of Aaj Aur Kal) was published in 1958. This made sense to me because by the late 50s and early 60s the public sentiment of the youth was all for change. India was a young independent nation. People had lots of ideas for freedom and reform, with the youth embracing democracy. The common men who believed in these notions were idealized not the princely state heads who were considered a bad hangover leftover from the British monarchy.

LikeLike

I’m so glad you liked it! *joyful dance* Tanuja is SO cute in this film. Although I cannot match her fire, she did at least inspire me to wear my hair in double braids for a few days after watching ( :

Thanks for adding the date of “Sundar Mi Honar.” It’s touching to hear how important Deshpande’s naataks were to your mother. Tell me, were the VHSs that she collected of ordinary live performances that had been taped, or (like the one I sent to Anup above) staged specifically to be filmed? The one I saw struck me as an interesting type of recorded play and I had wondered if it was part of a larger phenomenon.

LikeLike

Thank YOU for continually introducing me to new old movies that I haven’t seen yet! You are my movie guide! Also, now I want to put my hair in two braids!

The naataks were definitely staged to be filmed which is fascinating. At least the ones I have seen.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Shelomit, this is such a lovely review of the movie! I remember watching bits and pieces of it on television. But this is surely on my to-watch list. I can recall another movie dealing with the princely states which is completely different. It is Satyakam(1969) which is based on a Bengali novel, which is one of the best movies of Dharmendra and is directed by Hrishikesh Mukherjee. Not sure whether you have watched it.

LikeLike

Glad you enjoyed the write-up! Certainly this is a film worth watching in full.

I know “Satyakam” only for the song “Zindagi Hai Kya, Bolo,” on the basis of which I would never have guessed that it was set during the dismantlement of the princely states. Duly added to the watchlist! On the same topic, Anuradha’s recent post on K. A. Abbas had brought back to my mind “Aasman Mahal” with Prithviraj Kapoor.

LikeLike

He

This is Anagha, Dr Anup (mehefilmemeri), my brother introduced me to your blog. Nice review, I think I have watched Marathi play with Vandana Gupte and Girish Oak if I remember correctly. But now I will watch the film

Thanks

LikeLike

Good to have you here, Anagha ji! I enjoyed your “Mehfil Mein Meri” guest post on Brian Cox.

LikeLike

Thank you

I have started my own blog now. It is anaghasinterests on wordpress. I have given a title as A mixed bag

LikeLiked by 1 person