Ujala is constructed on the model of the classic ’50s social film a la Shree 420 or Jagte Raho. Unfortunately—aside from the fundamental disgrace of marooning Shammi Kapoor in what clearly wants to be a Raj Kapoor movie—it lacks both the heart and the political heft that lend such films their capacity to move. Left with little sympathy for its caviling hero, I found myself waiting increasingly impatiently for the next song. Ujala was produced by F. C. Mehra for Eagle Films. Its screenplay is by Qamar Jalalabadi from a story by director Naresh Saigal, with dialogues by Manohar Singh Sehraj.

Ramu (Shammi Kapoor) works as a porter to support his mother (Leela Chitnis) and a brood of younger siblings who, depending on the scene, vary in number somewhere between eight and three. The only ones that particularly matter are eldest sister Sandhya (Ratna) and littlest sister Munni (Baby Shobha). Circumstances conspire to place unforeseen demand on the family’s finances while simultaneously relieving Ramu of the handcart on which his business has relied. Ramu therefore takes up a standing offer from neighbor Kalu (Raaj Kumar) to join him in a strangely ill-defined petty crime venture. Chhabili (Mala Sinha), the dairymaid who for unfathomed reasons fancies Ramu, gradually badgers him into finding another honest job. Still, in a moment of desperation, Ramu runs one last errand for Kalu. This leaves him as a witness to a murder, all while the back rent is due and Sandhya needs her engagement bangles.

My thoughts on why this film doesn’t exactly work will require SPOILERS for the upcoming few paragraphs. Ujala proffers an explicit theory of the nature of crime, stated by the acharya (played by Shivraj) whom Ramu providently encounters in its second half. The acharya explains that nobody on earth is really a thug, a thief, or a pickpocket; people only turn to such evils in extremities. By way of the trust and implicit forgiveness the acharya extends to him, Ramu’s life very gradually gets back on track. There are without doubt passages and individual moments in Ujala that conjure the kind of trapped-animal pain that would naturally lead a person to rejigger their moral system. There’s Chhabili and Ramu’s quest to provide for Munni’s funeral and that slow, awkward, exhausting fight between Kalu and Chandu; even at the end, when Ramu finally recovers the ashram’s petty cash, he’s kissing the note like it’s a holy book. That’s the kind of imagery at which social dramas excel: depicting poverty (or some other structural condition) as a motivating force from which the bulk of humanity is helpless to escape.

The rest of the film does not tend to uphold the acharya’s assertion. In the first place, Chhabili clearly has a point when trying to convince Ramu that he is neither out of honest options nor as friendless as he imagines. At one point, after Ramu’s mother has learned about his stint with the gang, he snaps at her, asking whether she would possibly have been able to get Sandhya married if he wasn’t around to provide for them. Yet it’s Chhabili who both sources a dowry-free match for Sandhya and pays for her engagement bangles after maa has hocked her own wedding jewelry. Similarly, when Sandhya and her mother start working for a neighbor, it’s a horrible affront to Ramu. In fact, I’m confident that “horror” is exactly what that scene is attempting to convey, with the black grease on their hands looking so similar to Munni’s blood.

In the second place, the narrative puts Ramu and Kalu on parallel tracks and then makes no effort to explain why only one would be salvageable. Just to look at them, I would have thought Kalu was meant to be worse off than Ramu; his suit jacket spouts extravagant puffs of loose lining and, well, Raaj Kumar can look pinched when he needs to while Shammi, g-d bless him, cannot. Ramu and his chum Bholu (Dhumal) hold their gang’s honesty in high regard, lending money where the lala won’t and providing some sense of justice where the police don’t care to. If filmi criminals lie along a “good-natured thief” to “plummy gangster” spectrum, Kalu is obviously meant to fall on the hither side. Yet in the second half of the film, Kalu suddenly becomes a quite different, more determinedly wicked creature. I would have expected the acharya to expound on why that would be—perhaps something about need vs. covetousness, or theft vs. violence, both of which feel like nascent themes here. No; like the ashram’s warden, Kalu suddenly exists solely to pummel Ramu with all the ill fortune of Job, thereby giving Ramu the chance to prove his forbearance, or the acharya his wisdom, or something.

To be clear, I don’t need my films to have sociological theses in them. It’s just that, when they do, I’d appreciate either more explicit support for said thesis or more room to challenge it. Ujala is at its most interesting in its early passages, during which the appeal of crime itself, or perhaps of Kalu himself, is an obvious enticement to Ramu. We learn in their first exchange that Kalu and Ramu have been acquainted since childhood and that Kalu is angling to reestablish a friendship; even before Munni’s accident, he is conspicuously solicitous of Ramu. Ramu keeps hearing Kalu’s voice in his head, including when he first resolves to join the gang; Kalu’s imagined perception of him is more compelling to Ramu at that moment than his perception of himself. “Tera Jalwa Jisne Dekha” reads convincingly as a comment on their relationship: the one who saw your magnanimity has become yours. All of this evaporates from the second half of the movie. To suggest that being bad is fun, or that being honest is lonely, would not fit comfortably in the ashram.

(SPOILERS hereby concluded.)

Poor Shammi, although very, very pretty, does not acquit himself well here. He does at least squeeze in a few proper shimmies in “Jhumta Mausam Mast Mahina” and “Chham Chham Lo Suno.” I also found myself disappointed and at times even annoyed with Mala Sinha’s performance. I can’t recall ever having seen her be so weirdly stiff and loud. Although I appreciated the character, all the eyerolling and simpering in her performance wore on my nerves. When Kumkum turned up in an early scene set in the gang’s den, I was delighted to learn that she had a named character and at least a little dialogue. Sadly, she all but disappeared after that singular scene. There are two songs picturized on her dancing, to predictably entrancing effect (“Tera Jalwa Jisne Dekha” and “Ho Mora Nadaan Balma.”)

If this film has a saving grace, it is the music by Shankar-Jaikishan. Besides the ones that I mentioned above, I especially liked “Suraj Jara Aa Paas Aa” and “Duniya Walon Se Dur,” both of which feature the characters imagining themselves in kinder worlds. “Suraj Zara Aa Paas Aa” follows directly on the charming opening scene of the film, in which Ramu makes believe with his little siblings that the fairies have brought them invisible food. As the family dances down the street, they acquire more and more hungry neighbors happy to indulge in the fantasy. “Duniya Walon Se Dur” comes after a scene in which Ramu, reluctant to reveal to Chhabili that he has been working with Kalu, instead jokes that he is on his way back from the mythical land of “Premnagar.” In the song, they describe the secluded world to which they wish to go, one full of plenty and gentleness. “Yaaron Surat Hamari Pe Mat Jaao” is also noteworthy for its interesting street scenes—at several junctures, you can see passersby gathering on the street corners and at windows to watch the filming.

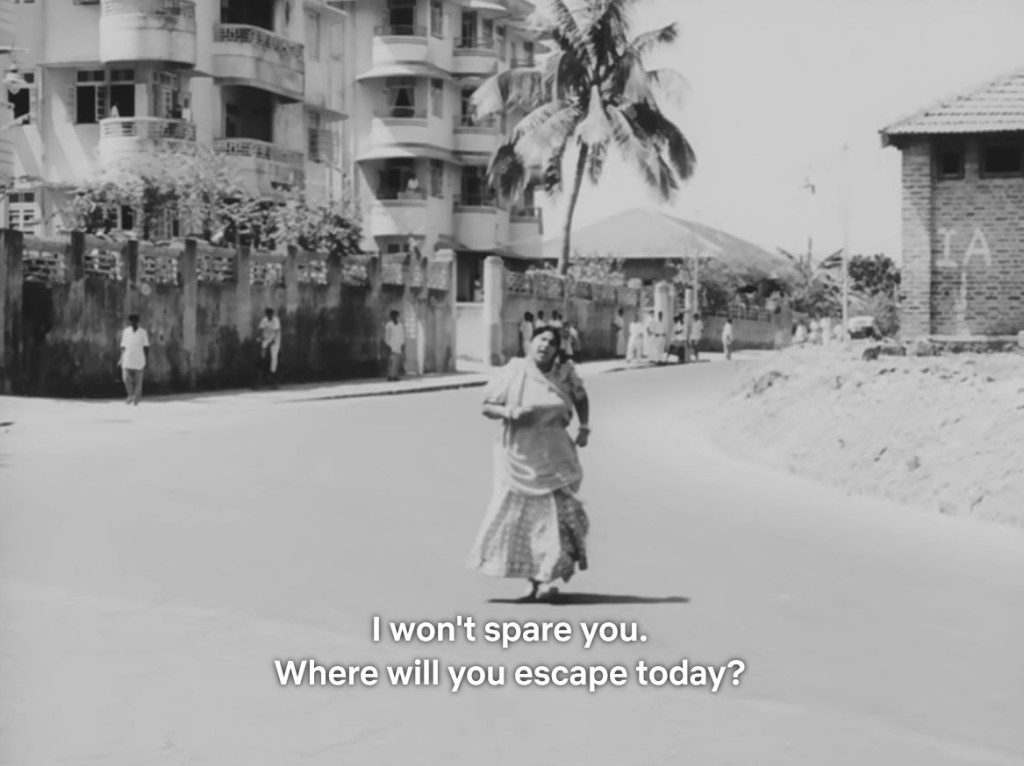

Finally, I want to mention a passage that I found compellingly weird. During “Yaaron Surat Hamari Pe Mat Jaao,” Bholu sits next to a washerwoman played by Tun Tun and slyly cuts the corner of her pallu into which she’s tied her spare change. (Are Ramu and Kalu meant to have put on this whole song and dance to distract from the stealing of a single purse? This is what I mean by “ill-defined petty crime”—!) When she realizes that she’s been thieved from, she takes off after the fleeing Bholu. Thus begins a strange freestanding comedic episode in which Tun Tun pursues Bholu tortoise-and-hare style. He has to stop and rest several times while she jogs doggedly behind him, never even breathing hard. It’s surprisingly long and almost entirely visually driven. I’ve never seen something quite like that in the middle of a Hindi movie! The very strangeness delighted me.

It’s been donkey’s years since I watched this (and reviewed it), so I have only the very vaguest memories of this film. Really, what I remember most forcibly is Tera jalwa jisne dekha, and Kumkum, so radiant. Shammi Kapoor – for whom I watched Ujala – was wasted on this one; you’re right about this being more the Raj Kapoor type of film than his.

LikeLike

“Ho Mora Nadaan Balma” is worth a revisit as well–her expressions are so beautiful and well-considered. I felt actively cheated when I realized Kumkum’s character of Kammo was only going to have a couple of scenes ( ;

LikeLiked by 1 person

I had forgotten about that song, and have just finished watching it. Lovely song, and yes, Kumkum’s expressions fit the scenario perfectly. She was such a joy to watch, always.

LikeLike

Shelomit, Ujala seems to be a movie which needs to be watched only for its songs. Thanks for this review!! Two things about the songs – three playback singers sing for Shammi- Rafi, Manna Dey and Mukesh. This is a little unique considering Rafi is the voice that is associated with Shammi.

Also the mukhda of this song seems to have been written to fit the metre – Yaaron Surat Hamari Pe Mat Jaon. Ordinarily it would have been Yaaron Hamaari Surat Pe Mat Jaaon.

LikeLike

One of my very favorite Shammi songs is sung by Mukesh: “Socha Tha Pyar Hum Na Karenge” from “Bluff Master.” Hemant sings for him as well in that movie, besides Rafi as usual. Jarring!

Thank you for your remark about the grammar of that mukhda. My Hindi is poor and I am always eager to learn more ( : From what you wrote, am I correct in understanding that “hamaari” still modifies “surat” despite appearing after the noun? If it went to “yaaron” instead, it seems like it ought to be in the form “hamaare.”

LikeLike